When sea turtles return to the coast after spending their early years in the ocean, they encounter a new threat: the risk of developing tumors. These cauliflower-like tumors are a symptom of fibropapillomatosis (FP), a debilitating cancer that affects all sea turtle species in Florida and worldwide. Costanza Manes, a graduate student in the University of Florida Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Department, studies how pollution may cause this disease.

“Coastal areas are heavily impacted by human activities, like pollution from power plants, river runoff, and urban, industrial and agricultural discharge,” said Manes, whose advisor is Ray Carthy, Ph.D., assistant unit leader in the Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, and CCS affiliate faculty. “It is only when turtles reach these disturbed environments that they develop symptoms, which is a hint that human activities could be a cause of this cancer.”

Sea turtles with FP can develop external tumors, such as those on their eyes, which can impair their vision and even cause blindness. Internal tumors may also form, and in severe cases, if these cannot be removed, euthanasia may be necessary. Although researchers have not yet identified the exact causes of FP, the disease has become alarmingly widespread, affecting 60 to 70 percent of sea turtles in some areas. When a population is this vulnerable, environmental changes put the species’ survival at serious risk, according to Manes.

To investigate the problem, Manes and her team collected 25 days’ worth of data in the field near Crystal River, Florida, at a location close to the Crystal River Energy Complex. They measured environmental factors such as temperature, salinity and pH. The team also recorded the concentrations of three categories of cancer-causing pollutants: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs). These chemicals persist in the environment for long periods and have previously been found in the blood of sea turtles with FP.

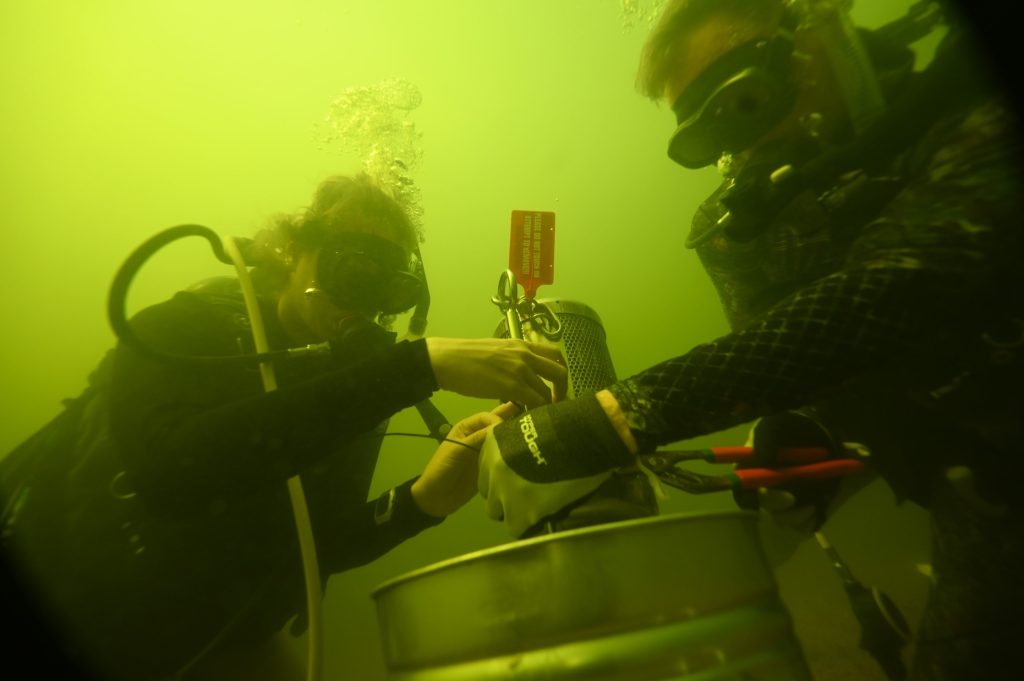

To mimic how sea turtles near Crystal River might accumulate these contaminants in their bodies over time, the team used semipermeable membrane devices (SPMDs). These are monitoring devices designed to capture pollutants while allowing most other molecules to pass through.

“We found all three classes of pollution in the water,” said Manes. “It’s sad, but we now have a basis to explain a potential cause of this disease.”

Manes is currently analyzing the data to identify patterns between pollutant levels and the prevalence of FP. She plans to present her findings at upcoming conferences, aiming to reach decision makers who can implement consistent environmental monitoring and cleanup efforts to protect both people and wildlife.

“We’re all connected,” said Manes. “All human activities and changes in the environment affect wildlife in a way that might somehow lead to the explosion of this infectious disease. Sea turtles are sentinels of the environment, so figuring out what changes in the environment are doing to them could also help us figure out what changes in the seawater and chemicals are doing to us. The wildlife is telling us a story.”

Project Information:

Project collaborators include staff from the Sea Turtle Conservancy (STC): Rick Herren, biologist and project manager; David Godfrey, executive director; Evan Cooper, membership coordinator; Margaret Lilyestrom, research assistant; and, Dan Evans, Ph.D., research biologist and sea turtle grants program administrator. Support from the University of Florida includes Costanza’s advisors Ray Carthy, Ph.D., assistant unit leader in the Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, and CCS affiliate faculty; and, Ilaria Capua, Ph.D., director at the UF One Health Center of Excellence.

This project was funded in whole by a grant awarded from the Sea Turtle Grants Program. The Sea Turtle Grants Program is funded from proceeds from the sale of the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate. Learn more at www.helpingseaturtles.org.

—

By Megan Sam