Nearly 90 percent of live coral has been lost in the Keys in the last 40 years, a stark reality that requires making informed decisions about how to invest restoration effort, according to Andrew Altieri, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Environmental Engineering Sciences Department, whose team investigates the impact of water quality and predation on coral restoration success.

“Some big questions are facing the Keys,” said Altieri. “Just like on land, where communities facing the damage of natural disasters, like a big hurricane, have to decide whether to rebuild stronger, differently or retreat. Given the challenges that corals are facing in the Keys right now from disease and heat wave events, people are asking if we should shift our effort towards different restoration sites or coral species, or consider how other conservation and restoration strategies should fit into the picture.”

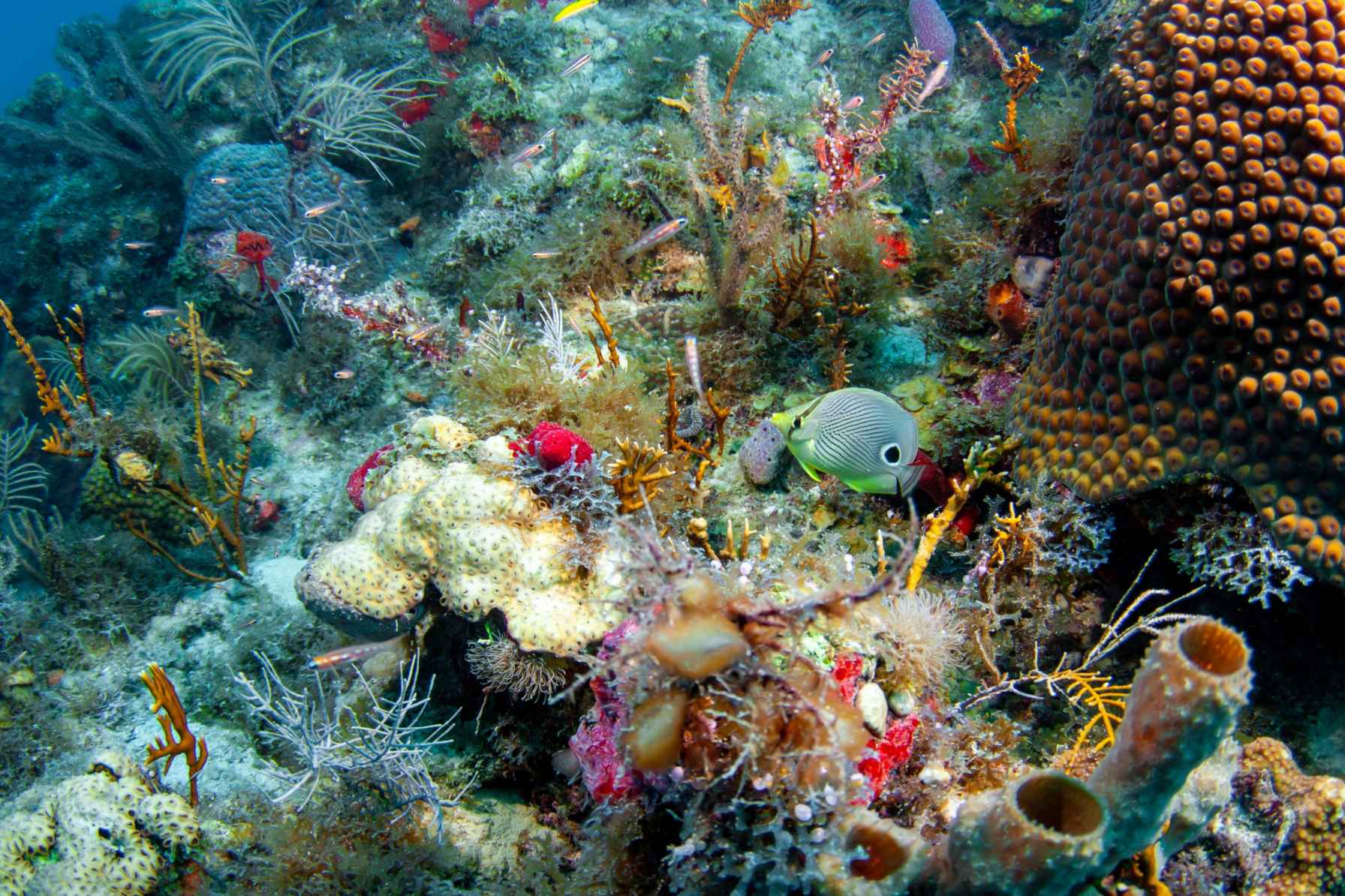

Florida’s Coral Reef is the third largest coral barrier reef in the world, spanning some 360 miles from the Dry Tortugas near Key West to the St. Lucie Inlet. This underwater tapestry of coral teems with diverse life, supporting thousands of marine species. The reef provides food to millions, protects coastal areas from storm impacts and contributes billions to the state’s economy, supporting thousands of jobs and generating billions in sales. This ecosystem also presents rich opportunities for scientific discoveries, including life-saving medicines.

In a race against time, researchers worldwide are looking into how to target restoration to help coral adapt to rapidly changing conditions. In southeast Florida, with support from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), Altieri is working with the Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium to examine how water quality and the presence of coral predators, such as fish and snails, impact coral restoration. These factors may limit where researchers can outplant corals and the success of coral restoration projects.

For the last two years, Altieri and his research team has conducted surveys every six weeks from May through October. Diving below the surface, CCS researchers track the growth and health of corals outplanted by the Mote lab the first summer, survey the size and population of fish communities in the reef, monitor organisms inhabiting the sea floor and measure water quality. During these surveys, four species of coral are monitored for health and any indication of bleaching. Altieri and his team will use the results to create products and publications to share with Mote Lab and other stakeholders regarding the species, sites and intervention strategies to increase the resilience of restored corals.

Launched in 2020, the coral reef research project parallels efforts worldwide to bolster coral restoration, an increasingly urgent challenge given the widespread demise and escalating threats facing corals. In the Keys, for example, scientists are finding that stony coral tissue loss disease, which causes the coral tissue cells to rupture and die, is now widespread. The effects of this disease, paired with the record-high water temperatures of this past summer, put this ecosystem under extreme stress, jeopardizing the likelihood of the long-term persistence of coral reefs in the Keys.

“The reefs of the future are going to look differently than the reefs of the past,” said Altieri. “What we need to figure out is how to strengthen those future reefs with our conservation and restoration efforts, rather than hold onto the reefs from the past. The systems are starting to change at a rate where it’s like a moving target, that’s why we need to be active with our discovery process and creative with our solutions.”

—

By Megan Sam