By Megan Sam

Just as probiotics can support human gut health, these beneficial bacteria may also play a role in protecting coral reefs. Often called the rainforests of the sea, coral reefs are teeming with life. But a mysterious disease, stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD), is devastating them faster than scientists can respond. A team from the University of Florida, the Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce, and Nova Southeastern University has discovered that applying probiotics can slow — and in some cases, stop — rapid tissue loss in corals affected by the fast-spreading, highly contagious SCTLD.

“What we found is that applying probiotics gave the corals a long-term benefit — either saving them from the disease or decreasing the amount of tissue they lost,” Julie Meyer, Ph.D., an associate professor in UF’s Department of Soil, Water and Ecosystem Sciences, said.

Corals, like us, depend on a diverse community of microbes that help them stay healthy by absorbing nutrients and helping remove waste. Because SCTLD spreads quickly and its cause remains unknown, the team explored whether naturally occurring bacteria could help corals fight back. Today’s most common treatment is an antibiotic paste that wears off within a few days and must be reapplied often, while also carrying the risk of contributing to antibiotic resistance.

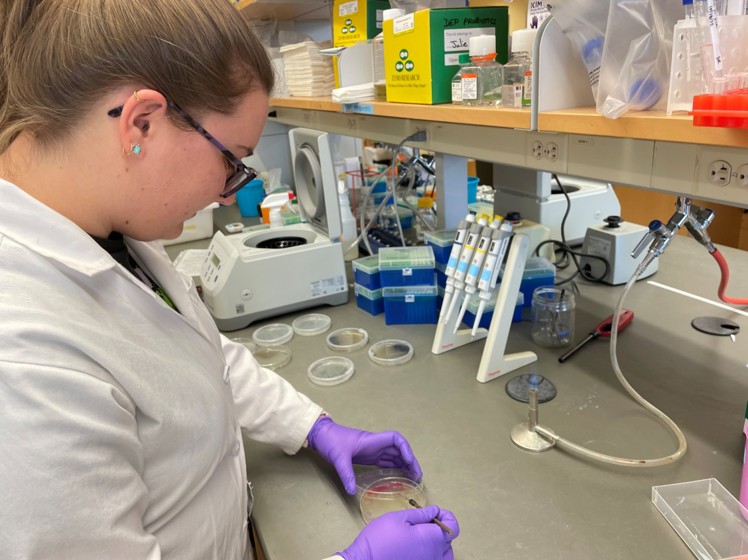

To search for a safer, more durable alternative, the researchers screened more than 4,400 bacterial samples for antimicrobial properties and examined the genetic makeup of 77 promising strains. One stood out: Pseudoalteromonas strain McH1-7. In lab tests, this probiotic stopped SCTLD from advancing and even prevented healthy corals from becoming infected.

The team then moved from the lab to field trials in Broward County. They tested two delivery methods on infected corals: a probiotic bag that enclosed corals in a bath of beneficial bacteria for several hours, and a probiotic paste applied directly to lesions. Control corals received sterile versions of both treatments. Over two-and-a-half years, scientists monitored tissue changes using photographs and three-dimensional models.

The results were striking. Corals treated with the probiotic bag lost far less tissue, about 20% compared to 75% to 80% in untreated corals. The paste, however, was ineffective. The beneficial effects of the bag treatment persisted long after the bacteria had disappeared from the coral’s surface, and the probiotic didn’t disrupt the coral’s natural microbiome.

“We think it’s working by disrupting the disruptors,” Meyer, an affiliate faculty member of the UF Center for Coastal Solutions, explained. “Many marine diseases are polymicrobial or involve multiple pathogens feeding on damaged tissue. By tipping the balance in favor of beneficial bacteria, Pseudoalteromonas lets corals strengthen their defenses and maintain a healthy microbial community.”

Field trials are underway in the Florida Keys, and the team is exploring new ways probiotic treatments could improve coral health.

“The fact that it worked — that we got the results we wanted — was exciting,” Meyer said. “Now, we’re building on what we learned about coral probiotics for disease to develop predictive or diagnostic tools for coral health in restoration projects.”