By Megan Sam

When Florida implemented a ban on foreign-manufactured drones in April 2023, researchers in the Ifju Lab at the University of Florida faced an unexpected setback. Much of their fieldwork, from underwater mapping to wildfire management, depended on the now restricted technology. Instead of turning to commercial alternatives, the team took a bold step: they designed and built their own.

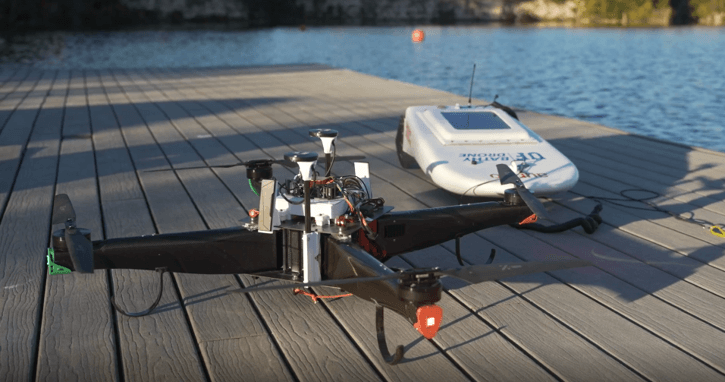

After two years of prototyping, testing and refinement, they created a high-performance, compact drone that not only rivals but exceeds the capabilities of most off-the-shelf models. It flies longer, carries heavier loads, and maneuvers tight spaces with ease. Paired with a tethered floating vessel, this system forms the Bathy-drone, a next-generation tool for high-resolution underwater mapping and surveys.

“The Bathy-drone delivers fast, precise surveys in small areas and can be operated solo — no boats, ramps or large crews required,” said Peter Ifju, Ph.D., a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at UF. “It’s also cost-effective and efficient compared to traditional methodologies. For example, a level pole might take eight hours to manually measure elevation points. The Bathy-drone can do the same in just 25 minutes.”

Designed for versatility, the system operates at speeds of up to 15 miles per hour, covers more than 20 acres per battery charge, and works in strong currents and dense vegetation without disturbing sediment or getting tangled.

The lab has already deployed the Bathy-drone at several sites in St. Augustine, Florida. In Cat’s Paw, a degraded salt marsh, researchers used the system to map the underwater terrain and measure the density of the riverbed floor, helping to guide restoration efforts aimed at reestablishing vegetation and preventing erosion. In the wake of Hurricane Milton in October 2024, the team deployed the Bathy-drone to assess storm damage on the Matanzas Inlet, Florida’s only naturally occurring, undredged inlet on the east coast. They later used the drone-based system in a salt marsh along the western shore of the Matanzas River, where traditional boat surveys would have been too invasive or impractical, to supplement data collected by engineering firm WSP for a marsh restoration project.

“In the marsh, it’s muddy, shallow, filled with oyster mounds, and sensitive to boat traffic,” said Joseph Sforza, a first-year mechanical engineering Ph.D. student in the Ifju Lab. “The Bathy-drone was the only tool that could conduct a widespread, non-invasive survey in this environment.”

Beyond advancing coastal research, the Bathy-drone project has become a powerful learning platform for students. By working hands-on with cutting-edge drone systems, students gain practical experience that bridges the gap between theory and real-world problem-solving. Sforza, who serves as a drone pilot for the lab, says the field experience has positively influenced his career path as a mechanical engineer.

“I’ve always been interested in robotics and autonomous vehicles,” said Sforza. “It’s been really exciting to see the classroom concepts come to life in a system that solves real problems.”

Jack Parker, a recent graduate, echoes the value of hands-on learning.

“It’s been incredible to take an idea from a brainstorming session all the way to a working solution,” said Parker, who is currently a research assistant for the UF Center for Coastal Solutions and the Ifju Lab. “We’ve been able to apply what we’ve learned in class and push it even further.”

Up next, the team is working on a foldable version of the drone to make it easier to transport and deploy in the field. They’re also integrating new sensors to detect water flow and monitor water quality, expanding its potential for environmental research and monitoring.

“The Bathy-drone is an incredible system,” said Sforza. “It’s far beyond anything else out there for surveying hard-to-reach water bodies. It really feels like a glimpse into the future of environmental surveying.”

To learn more or explore how the Bathy-drone could support your surveying needs, reach out to Peter Ifju at ifju@ufl.edu. To explore data-driven tools that enhance environmental outcomes and maximize return on investment, visit https://ccs.eng.ufl.edu/what-we-do/products/.