Five years ago, Hurricane Michael caused massive damage to Tyndall Air Force Base when it carved through the Florida Panhandle. Today, the base is wielding nature’s power to increase the military installation’s resilience against future climate and extreme weather events.

As part of the base’s $5-billion rebuild program, researchers from the UF Center for Coastal Solutions are monitoring ecosystem conditions to guide the design, location and construction of living shorelines and the restoration of seagrass beds as a first line of defense for the base against future hurricanes.

“Nature-based coastal defenses integrate natural ecosystems like seagrass meadows, oyster reefs, marshes and dunes, with conventional coastal protection schemes,” said Beatriz Marin-Diaz, Ph.D., a postdoctoral associate at CCS, who leads a research team collecting ecological data. “They can be a more resilient and sustainable solution in the face of global change.”

Seagrass meadows play a vital role in coastal ecosystems by filtering water, stabilizing bottom sediments to prevent erosion along the coast, and providing habitat and shelter for many organisms. They store large amounts of carbon and slow waves down, further protecting coastal communities and ecosystems from damage caused by storms.

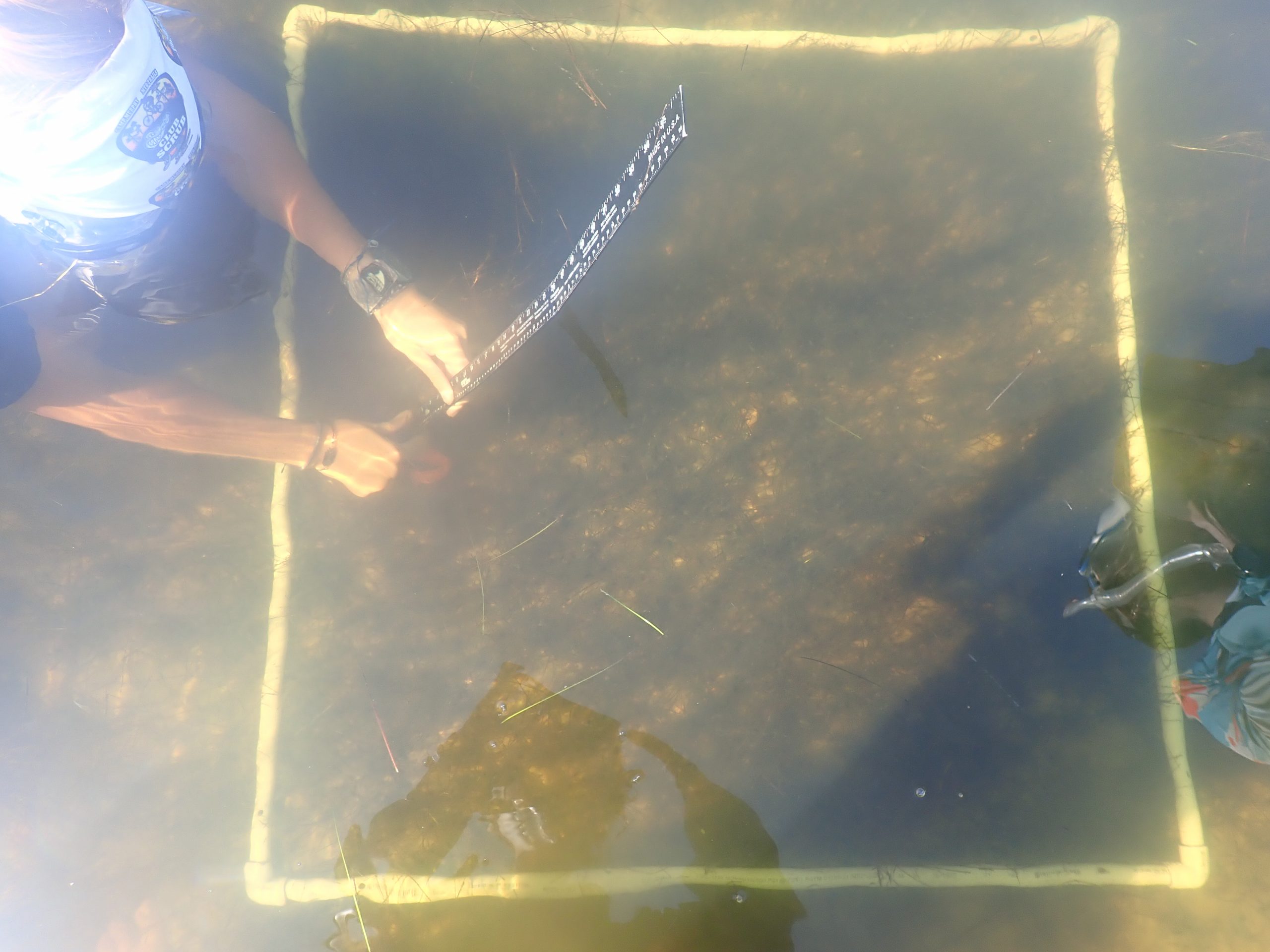

Marin-Diaz’s team monitors seagrass percent cover and surveys areas for seagrass restoration. In locations where seagrass does not grow, the team is investigating two potential reasons: sediment movement and ground disturbance from stingrays that prevent the seagrass from establishing.

The Nature Conservancy, one of the project partners, will use the data to guide seagrass planting. This will provide additional coastal protection to the base by reducing the impact of waves.

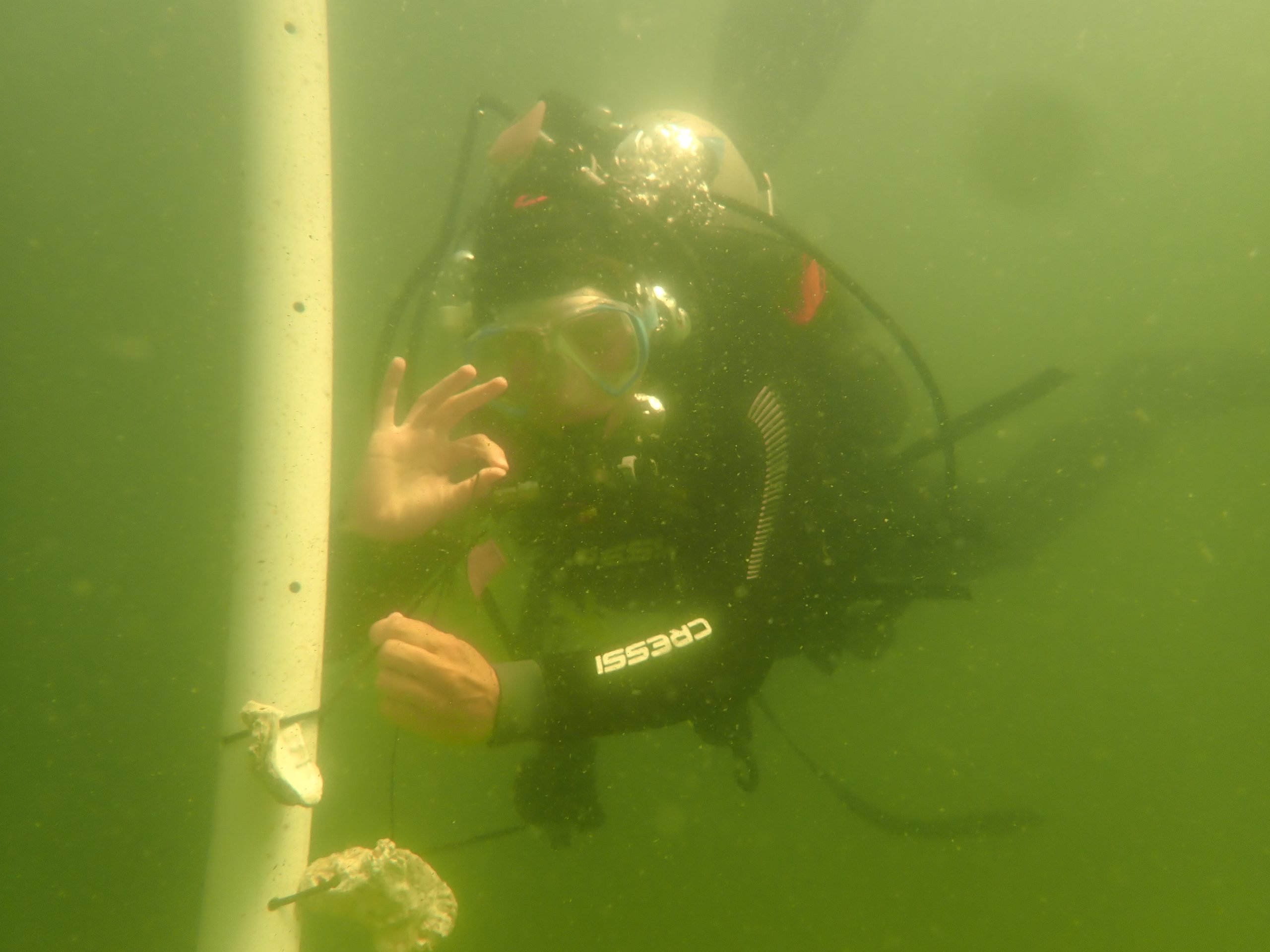

The team is also collecting data to assess the suitable depth for oyster recruitment, the process by which new oysters settle onto a substrate, which is the surface the oysters grow on. This data will be used by its collaborator, Jacobs Engineering, to inform the design of living shorelines in Tyndall. These living shorelines will include implementing hard substrate where oysters can settle and build a new reef. The goals of living shorelines is to create new habitat and reduce wave energy and erosion of the shoreline.

This research is part of a project in collaboration with the Naval Research Laboratory, The Nature Conservancy and Jacobs Engineering. This ambitious project includes plans to build up to 1,000 feet of living shorelines and up to 3,500 feet of submerged shorelines — comparable to the height of the Empire State Building and Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world, respectively. These initiatives will mitigate habitat loss as well as create an additional 1,500 feet of oyster reef habitat.

“The data is looking good inside St. Andrew’s Bay” said Marin-Diaz. “There are oysters recruiting, and the seagrass meadows look healthy. However, is not the case for the seagrass meadows in St Andrew Bay Sound, which have been retreating after the hurricane.”

These pilot projects will provide the military with invaluable information to inform the implementation of nature-based solutions to make coastal areas more resilient in the face of global change, with possibilities for expansion in Tyndall Airforce Base and other similar installations.

Related: Defending the Gulf With Nature

—

By Megan Sam