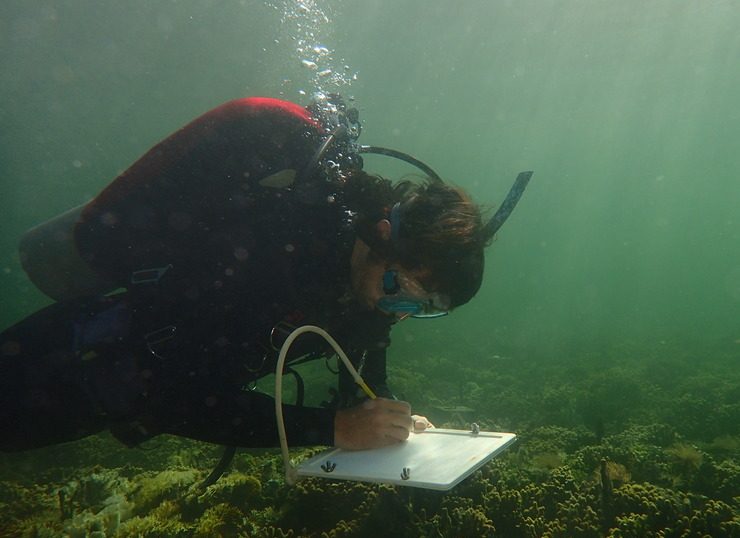

Patrick Saldaña has turned his passion for all things ocean — from diving in sunlight dappled kelp forests to spearfishing off the coast of California — into a career studying the history and future of marine ecosystems around the world. Saldaña, who graduated in May with a doctorate degree in environmental engineering sciences from the University of Florida, investigates the importance of dead foundation species for biodiversity, ecosystem function and resilience. Saldaña’s research has taken him to Bocas del Toro in Panama, a heavily developed Caribbean island that has seen the loss and deterioration of its coral reefs since the early 20th century.

“The reefs in Bocas are in a very human impacted system and it’s likely that other Caribbean reefs will end up looking similar,” said Saldaña, Ph.D. “We believe they represent a fast-tracked version of where coral reefs are going because of the history of human stressors, from banana plantations a hundred years ago to the booming tourism industry now. Understanding why a significant amount of coral persists in some areas is important to predict the course of future reefs.”

Dead foundation species, which create habitats, have been largely understudied in marine ecosystems. Saldaña found that dead corals are active parts of ecological communities and when their numbers are high, can attract bioeroding organisms such as reef urchins that structurally damage the reef framework. This suggests that dead corals should be integrated into more monitoring efforts, experiments and models to better understand how reefs are responding to global change. And not just corals: his research also revealed that all dead foundation species continue to play a role in nearly every ecosystem and should be considered in ecosystem restoration and future predictions.

As a postdoctoral researcher, Saldaña will continue working with his advisor and assistant professor Andrew Altieri, Ph.D., in the environmental engineering sciences department, on projects that arose from his graduate studies and also work on developing a model that predicts how the structure and species makeup of coral reefs in Bocas will change over time.

“I’m excited to use the data that I collected over the last several years from experiments and monitoring, and incorporate them into predictive models of different reefs in Bocas,” he said. “I love learning about these systems and having the chance to produce new knowledge that can hopefully benefit the environment and humans’ relationships with it.”

—

By Megan Sam