Earlier this summer, researchers from governmental, academic and nonprofit organizations gathered in the Florida Panhandle to compare notes on their latest research findings for the region. Their purpose? Building a collaborative network and identifying priority projects and funding opportunities to rehabilitate the region’s shorelines and reverse water quality declines.

Researchers at the University of Florida’s Center for Coastal Solutions (CCS) recently wrapped up a major research project, sponsored by Senator Doug Broxson, in which they investigated how best to improve water quality and lessen economic impacts of water declines in Northwestern Florida. Eager to share their findings and implement next steps, CCS organized a regional planning summit to gather researchers, natural resource managers and nonprofits working on related projects with the shared goal of changing the trajectory of coastal communities in the region.

“Today is really important because one of the main goals of this project is to get large-scale, collaborative grant proposals funded that can help bring money in to benefit these local communities,” said Savanna Barry, a regional specialized extension agent with UF and Florida Sea Grant. “There’s a lot of capacity on the ground to do this kind of work but getting them all in the room and talking and prioritizing where they would like to collaborate is what we’re doing today and that is an important task.”

Integrating diverse expertise to change the trajectory of Florida’s coasts

To paint a holistic picture of the current situation, participants shared their research findings on different aspects of Florida’s shorelines, including current water quality issues, threats to biodiversity and the region’s economic status. With the data on the table, the conversation turned to how the network could tap into available funding opportunities to harness the expertise and strengths of their individual organizations to address coastal issues on a regional scale.

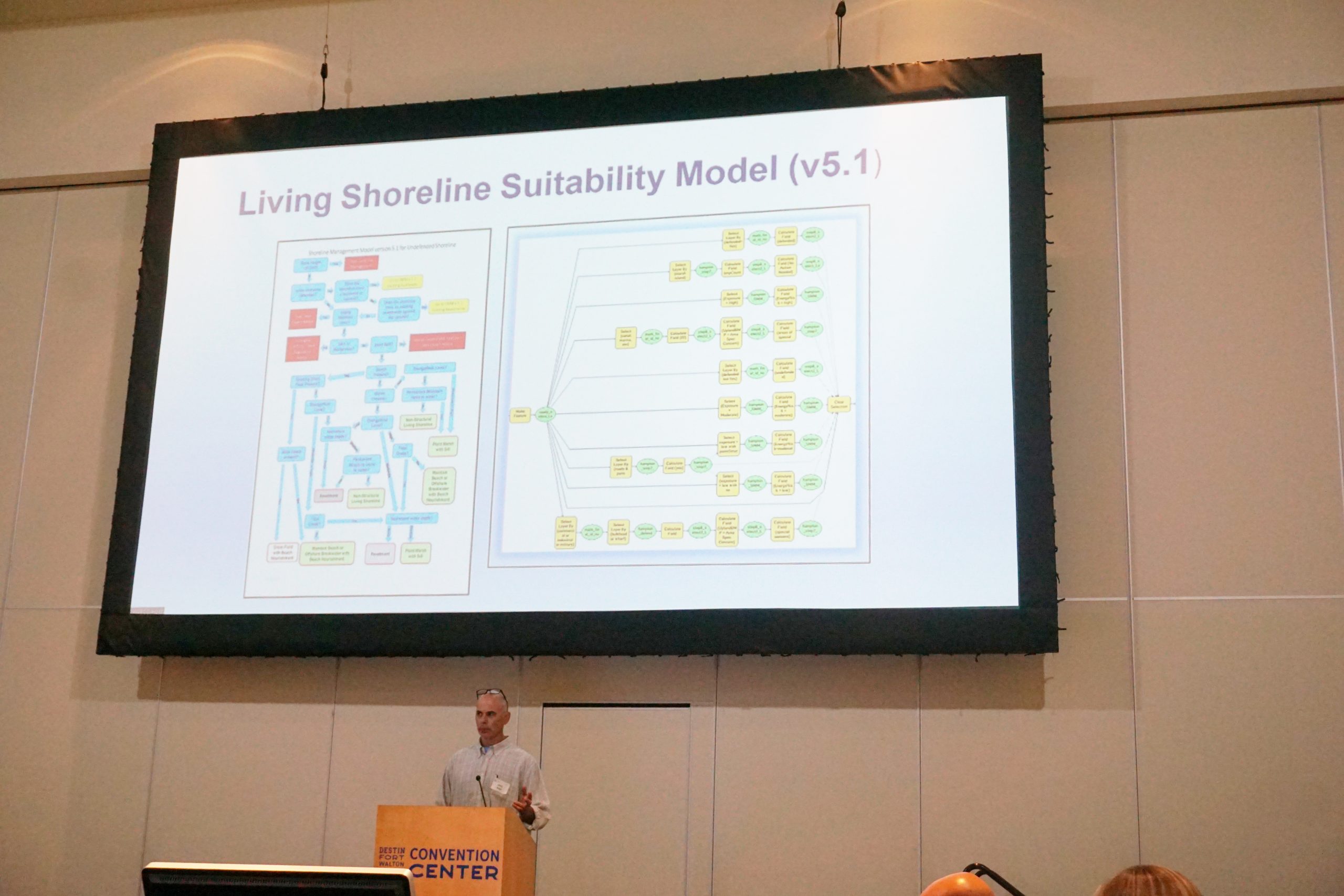

Going forward, attendees committed to a nature-based approach for improving shorelines in their region by building up “living shorelines,” as opposed to seawalls or other gray infrastructure options. Barry and Chris Boyd, a professor at Troy University presented their results from a living shorelines suitability model that would support the participating organizations in mapping out new projects to meet their common goals.

“I think living shorelines are important environmentally,” said Tricia Kyzar, a researcher and project manager at CCS. “To me, it seems very intuitive that you would prefer natural environments over artificial ones, like hardened shorelines. Nature knows a whole lot more about how to manage these things than we do, and they’re prettier than a concrete barrier.”

Not only do living shorelines look better, but they also provide incredible benefits for the environment. Living shorelines are natural defense systems, protecting coasts from major storms by reducing wave energy.

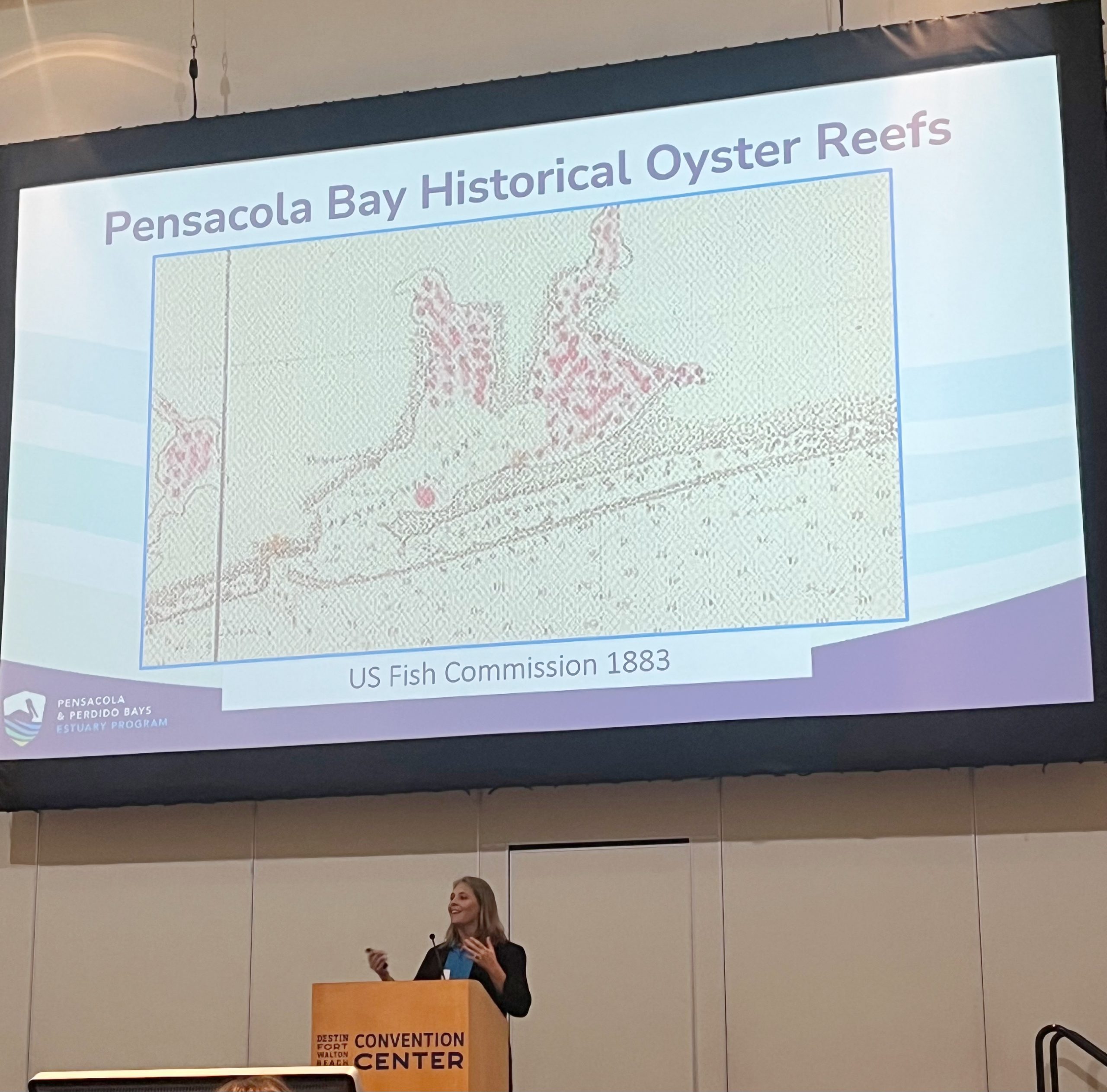

Haley Gancel, an environmental scientist with the Pensacola & Perdido Bays Estuary Program (PPBEP) talked about her team’s efforts to restore oyster reefs, which are often incorporated into the design of living shorelines. Poor water quality has dramatically reduced Pensacola Bay’s historical oyster reefs. By incorporating a habitat suitability model into the living shorelines model, the project will improve the oyster population and promote a sustainable fishery, as well as a healthy natural environment.

“Projects like living shorelines, especially on a regional scale, one group by themselves is not going to be able to do this,” said Gancel. “Different organizations have different tools in their toolbelts to get some of this going. In our region, we don’t like to work in a silo; we like to work with all of our partners for the greater good of our economy and economic resources and natural resources.

A brighter future for Florida shorelines

Living shoreline suitability and prioritization models are representative of what regional organizations can accomplish if they work together. By improving water quality and reinforcing natural habitats, living shorelines will cultivate flourishing environments that improve the health of underwater communities and those depending on coastal resources for their work and wellbeing. Now that they are on the same page, the participating organizations are ready to move beyond the drawing board and bring their plans to life.

“I think the future is bright for Northwest Florida!” said Dr. Christine Angelini, director of CCS. “The region has highly motivated and experienced individuals and organizations that know how to get projects designed and delivered and are committed to working together to pursue the big investments required to sustain water quality, biodiversity and natural resources. These natural resources are the foundation of the region’s economy and essential to the quality of life of local residents.”

CCS is encouraged by the strong relationships established at the event and hopeful for significant progress in the rehabilitation of Florida shorelines.

“My goal is for the Center for Coastal Solutions to continue to engage with our network of stakeholders and researchers to apply our expertise and world-class research infrastructure to bolster the science that the region has access to as it makes big decisions about how to manage its coastline in the future,” said Angelini. “I see particular value in working with our partners to identify what the compilation of coastal habitat restoration and shoreline stabilization projects should be that will achieve the highest returns on investment in improving the quality of life of local residents and environmental resilience.”

—

By Holly Sproule