Researcher and educator Nina Stark has crisscrossed the world to help coastal communities build more resilient infrastructure in the face of rising coastal hazards and climate change-related threats. Her expertise in marine geotechnics, the mechanics of seabed sediments, has taken her from the frigid and windy conditions of the Arctic to the sunny Florida coasts.

“Since I get to do field work all over the globe, I think I’ve visited some of the most unique places in the world during my job,” said Stark, Ph.D., who joined the Geosystems Engineering program as an associate professor in the Department of Civil and Coastal Engineering in August. CCS also extends a warm welcome to Dr. Stark as our new affiliate faculty member.

One such place is the Ahr Valley in Germany, where Stark co-led a project to document how the soil beneath and around affected infrastructure moved and interacted with flood water, infrastructure and debris during extreme flooding. This work supports a growing need for infrastructure design updates and flood mitigation strategies in response to climate change.

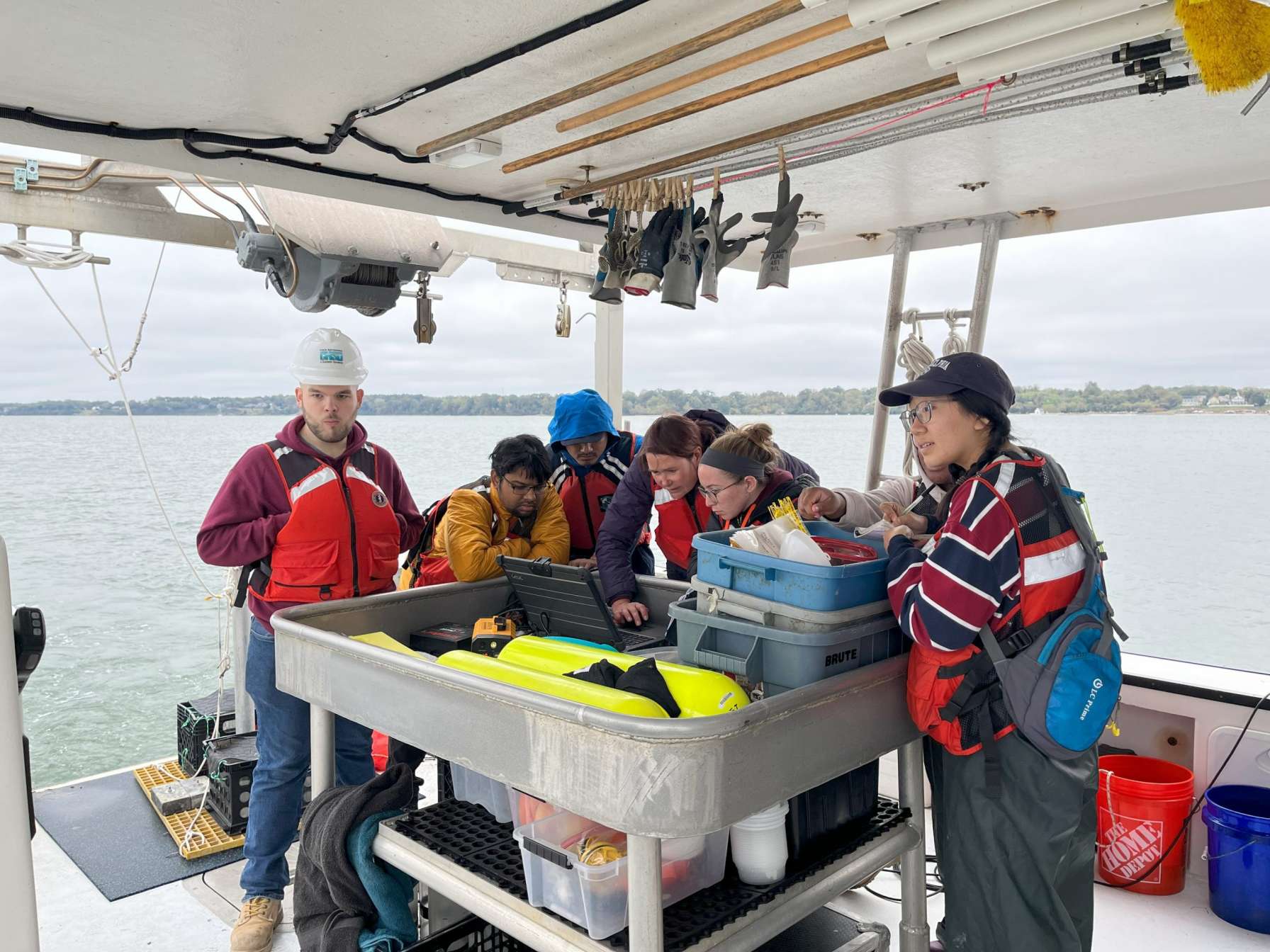

In addition to research, Stark finds it rewarding to provide students with accessible, experiential training that helps prepare the next generation of leaders in coastal fieldwork. In 2019, she led an undergraduate field experience program to Alaska that focused on understanding coastal erosion during extreme events and sea level rise, as well as introduced undergraduate students to research for naval applications.

The program intentionally recruited female students and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. To remove barriers, students received funding support, which enabled them to focus fully on learning and gaining experience in the field. After the program, 50 percent of participating students reported that the experience was beneficial to their careers and over 25 percent applied for a STEM graduate school program.

“A goal of mine is to reach students who think they cannot get to where they want to be,” said Stark.

Stark’s research has three major thrusts. The first is looking at the behavior of seabed sediments with applications for coastal hazards, such as understanding seabed mechanics to engineer structures that can withstand extreme flooding and ocean forces.

Stark also carries out research related to naval applications. For example, she studies beach trafficability, or how easily vehicles can move across the beach for various operations without getting stuck or damaging the environment. She has also led projects to develop methods for assessing the risks posed by unexploded ordnances (weapons that may still detonate) on beaches by characterizing the seabed soil in order to detect their location and predict the interaction with the seabed.

Stark’s third area of investigation is predicting how coastal landscapes will change to support navigation, for example, how boats can move through areas where the landscape has changed from flood events.

“To improve the prediction of changes in seabed conditions, erosion, deposition, hazards and changes to navigation are worldwide a big challenge, in particular in a changing climate,” said Stark. “The University of Florida and the Engineering School of Sustainable Infrastructure and Environment have a strong reputation in coastal research, and I’m excited to expand on my interdisciplinary work and collaborate with different CCS faculty to work on projects that have an even wider range of applications.”

—

By Megan Sam